16 February 2018

I gave a presentation at MOBOS conference in Cluj-Napoca, Romania this week. It was based off some work I did last year, but have since added a lot of new features.

The slides didn’t have any text, so here’s a summary of what I presented.

We’re working on an app for a video-on-demand/TV catch-up service.

Our team includes developers, QA and design. There’s strict process about PR review.

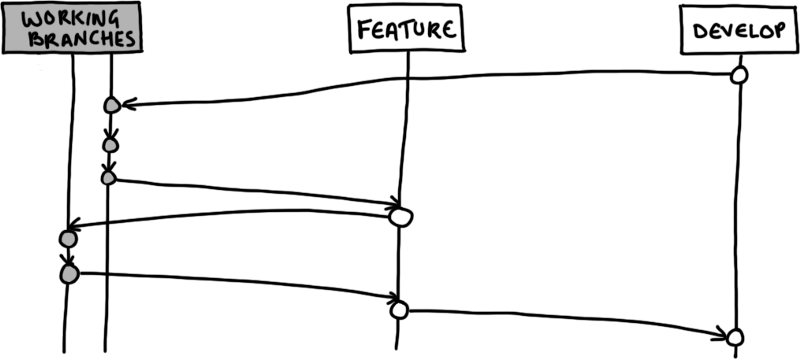

We follow something similar to gitflow though we do not allow direct pushes to the feature branch. Instead, we commit to “working branches”, raising pull requests against the feature branch that must be code reviewed.

Once all subtasks are complete and the feature has been implemented, that’s where QA come in.

We raise a PR to merge the feature branch into develop, and this is where QA will test the feature to ensure it meets the acceptance criteria and does not introduce regressions.

It’s a lot of effort–there are automated tests which are run as well as new ones which are added. The majority of the regressions come in the form of UI related bugs: either unintended changes in appearance, or elements which which should be displayed not displaying and vice versa.

To reduce the number of UI regressions:

The first part is difficult for QA to check from the outside of the app, since they will need to provide many variations of mocked network responses to validate the app behaviour. For us, it’s easier since we can create these view models in our tests, and make assertions using Espresso.

Here’s what typical Espresso test looks like:

@RunWith(AndroidJUnit4.class)

public class SeasonActivityTest {

@Rule

ActivityTestRule activityRule = new ActivityTestRule<>(SeasonActivity.class);

@Test

public void myTest() {

// ...

}

}

The ActivityTestRule is an example of a JUnit Rule. It creates and launches an activity (SeasonActivity in this case) before each test, and finishes it after each test has completed running.

We wrote a ViewTestRule that extends the activity one. You pass in a layout resource, and the rule will launch an empty activity, inflate and add the layout to the root, and then otherwise behave as the ActivityTestRule.

@RunWith(AndroidJUnit4.class)

public class EpisodeItemViewTest {

@Rule

ViewTestRule viewRule = new ViewTestRule<>(R.layout.item_view_episode);

@Test

public void myTest()

// ...

}

}

This is not enough on its own (in most cases) because the inflated view will have no data bound to it. We can instantiate the class the binds data to the view, in this case, EpisodeItemViewHolder, passing the subviews as dependencies using viewRule.getView() to get the root.

@Rule

ViewTestRule viewRule = new ViewTestRule<>(R.layout.item_view_episode);

EpisodeItemViewHolder holder;

@Before

public void setup() {

View view = viewRule.getView();

holder = new EpisodeItemViewHolder(

view,

view.findViewById(R.id.title),

view.findViewById(R.id.subtitle),

view.findViewById(R.id.badge),

view.findViewById(R.id.poster)

);

}

Now we can write a test! We use a TestEpisodeBuilder which has default values, then modify the ones that are important for that test.

@Test

public void hideSubtitle_ifNotPresent() {

Episode episode = new TestEpisodeBuilder().withoutSubtitle().build();

viewRule.runOnMainSynchronously(view -> holder.bind(episode));

onView(withId(R.id.subtitle)).check(matches(not(isDisplayed())));

}

The viewRule.runOnMainSynchronously(...) is necessary because when the holder binds, it’s modifying the view. Since the view was created on the main thread, it can only be modified on that thread.

There is an annotation that is meant to run tests completely on the main thread, which I thought would be fine (@UiThread) but although I don’t get any crashes with it, the test does not complete–it just runs until it’s cancelled (I didn’t wait for it to time-out). So that’s the reason we wrap the bind in that method explicitly.

Since we’re just testing that our Views are wired up correctly, we can use mocks to make sure that interactions are also bound as expected:

@Test

public void clickingOnItemView_invokesListener() {

Listener listener = Mockito.mock(Listener.class);

Episode episode = new TestEpisodeBuilder().withListener(listener).build();

viewRule.runOnMainSynchronously(view -> holder.bind(episode));

onView(ViewTestRule.underTest()).perform(click());

Mockito.verify(listener).onClickEpisodeWithId(episode.id());

}

We use the click() action from Espresso to click on the item view and then verify that the correct method was invoked with the expected parameter.

Our partner wanted to add better support in the app for users with disabilities.

Awesome! How can you go about such a request in your own app? I would start with what you know.

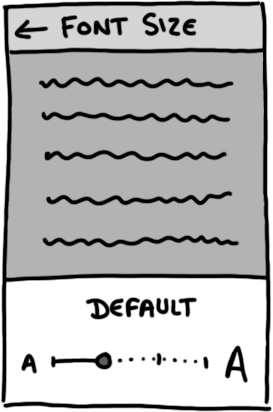

Android developers will have learned to use sp (scaleable pixels) for text instead of dp (density-independent pixels). This means that when the user increases the system font size, text that has size specified in sp will grow, whereas text with size specified in dp will remain the same.

| Font size - default | Largest |

|---|---|

|

|

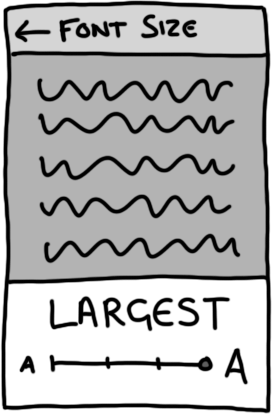

A common defensive mechanism for ensuring that text does not get clipped in fixed dimension layouts is setting the android:ellipsized="end" property on the textview:

Although this makes the clipping look intentional, it means that text is not readable anymore. Instead, we should try to make our layouts responsive. The simplest way to do this is to use the wrap_content value for the container. This is sometimes not possible–consider whether using sp to define View dimensions is reasonable, as this will allow the container to grow with the text:

Check periodically that your app doesn’t break with variations in system font size.

We wrote a rule that can change the system font scale. Combining an ActivityTestRule or ViewTestRule with screenshots, we can get a set of pictures with our app at different font scales to check if any of our layouts break:

ActivityTestRule activityRule = new ActivityTestRule<SeasonActivity>(SeasonActivity.class) {

@Override

public void finishActivity() {

SystemClock.sleep(160); // keep on-screen long enough to capture

screenShotter.capture("episode-huge") // with file prefix

super.finishActivity();

}

};

@Rule

RuleChain ruleChain = RuleChain

.outerRule(FontScaleRules.hugeFontScaleTestRule())

.around(activityRule);

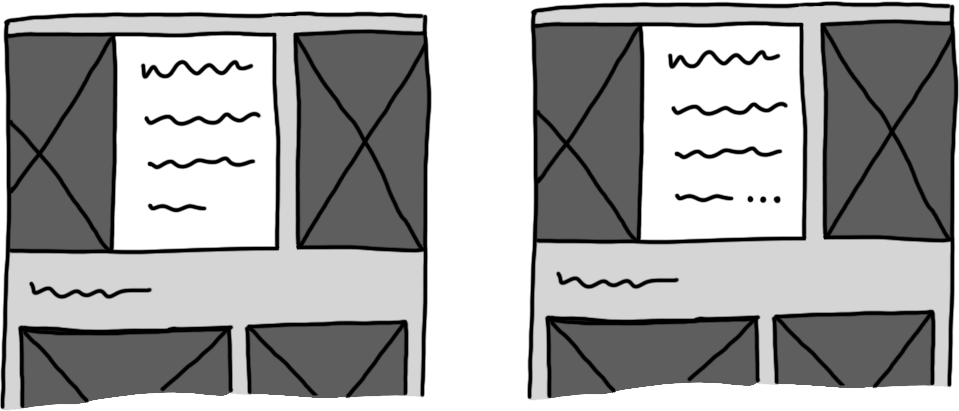

Consider how users of assistive technologies will interact with and navigate through your app. These indirect interaction methods include:

For many of these indirect interaction methods, navigation through an app is linear or sequential, focusing on actionable items.

This can be frustrating when dealing with a list of views that each have inline actions.

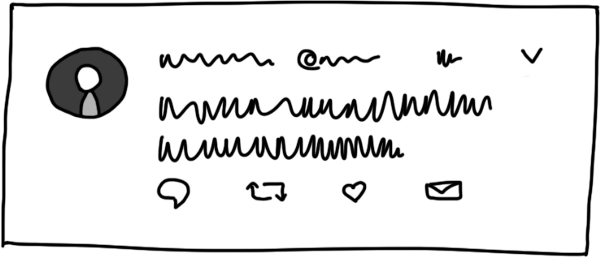

Consider a tweet, which has six inline actions in addition to the item view action:

Navigation using a Switch Access device through tweets in the feed would take seven steps per tweet.

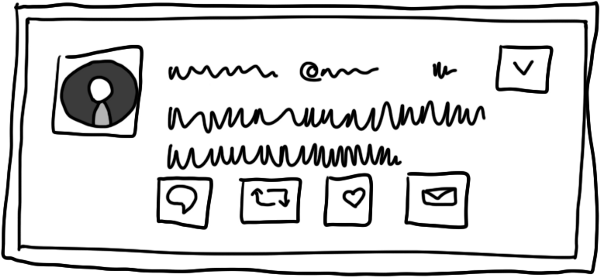

We can inflate a different layout (or modify the existing layout) if we detect an accessibility service is running or if the view is in non-touch mode, removing all the inline actions, which means navigation would take one step per tweet:

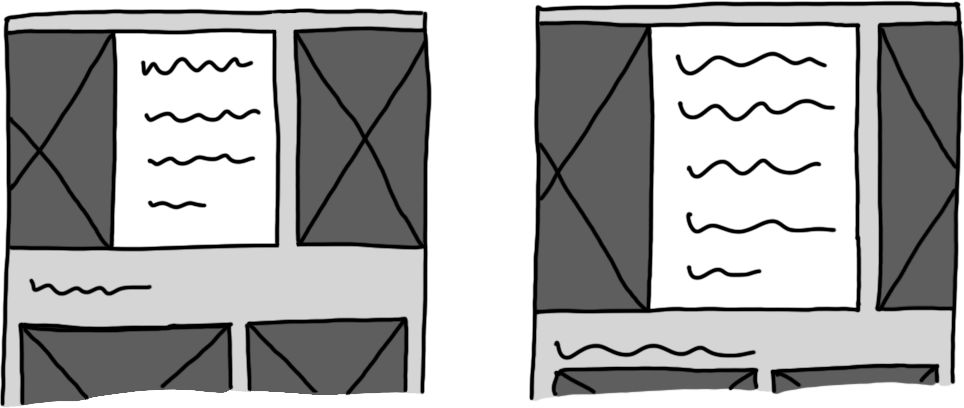

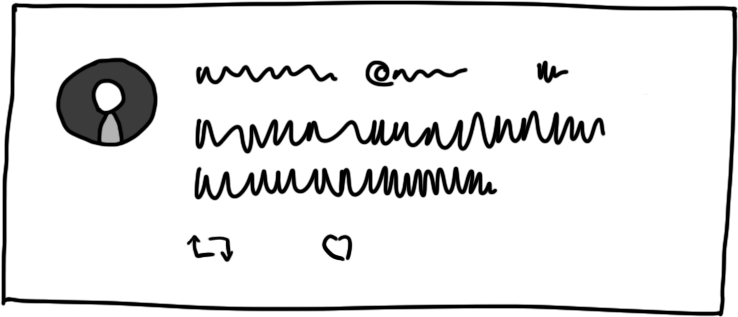

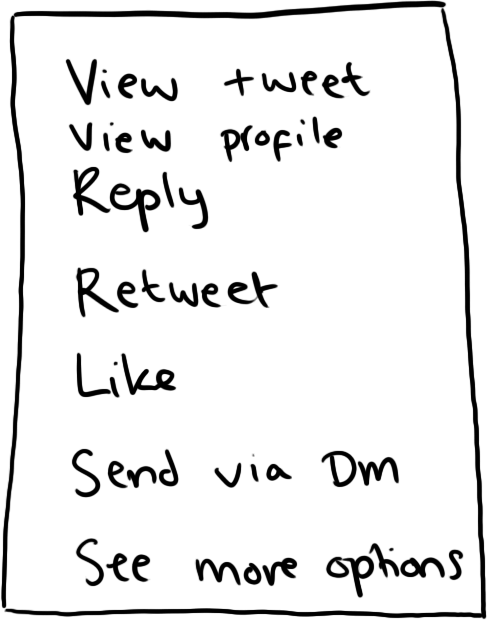

Of course it’s no good removing all the actions–we’re trying to make our app accessible and usable so we can’t just remove access to features. Instead, we present them in a list dialog when clicking on any item view:

After doing this for each list in the app with inline actions on item views, imagine QA’s reaction to having been told they’ll have to test it and add it to their regression test procedures.

Well, we can test some of this now with Espresso. Although we’ve had a test rule that turns TalkBack on and off programmatically for a while, we’ve recently added the AccessibilityRules factory.

This contains rules for known accessibility services which we can turn on and off–this lets us test any custom behaviour in our Activities and Views.

ViewTestRule viewRule = new ViewTestRule<>(R.layout.item_view_episode);

@Rule

RuleChain ruleChain = RuleChain

.outerRule(AccessibilityRules.createTalkBackTestRule())

.around(viewRule);

I told a story in which I found it difficult to put my bins out:

The story concluded with the point that we should test our apps in various situations, e.g. in areas with lots of light and areas with very little light, since this can raise issues with color contrast.

Color contrast is a measurement of the difference in lightness between two colors.

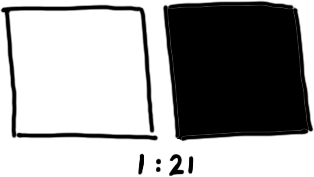

It ranges from 1:1, which is for two colors that are the same, to 1:21, which is the contrast ratio of black and white (or white and black).

| Low contrast | High contrast |

|---|---|

|

|

We’re working on adding a TextView assertion to grade the color contrast given the background of the test. This is difficult because:

But we can probably do some naive implementation that will work for 80% of the cases.

Then I summed up the three things you can start to look at in your app and how to test them:

The things I’m still working on/looking to understand:

ViewAssertion that would determine whether the text from a textview has a great enough contrast with its background, based on the size of the textWRITE_SECURE_SETTINGS permission at runtime with an adb command inside the accessibility test rules, like we do for WRITE_SETTINGS for the FontScaleRuleUiThread annotation doesn’t work as I expect (to get rid of viewRule.runOnMainSynchronously(...))Start using the espresso-support library today and let me know what you think.